- Home

- Newt Gingrich

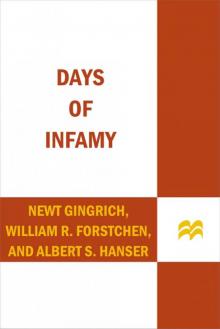

Days of Infamy

Days of Infamy Read online

Praise for Days of Infamy

“Skillfully combining historical characters with fictional ones, Gingrich and Forstchen have crafted a riveting, exciting, and realistic novel of World War II.”

—Library Journal

Praise for Pearl Harbor

“A thrilling tale of the attack that marked America’s darkest day.”

—W. E. B. Griffin

“Masterful storytelling that not only captures the heroic highs and hellish lows of that horrific day which lives on in infamy—it resonates with today’s conflicts and challenges.”

—William E. Butterworth IV,

New York Times bestselling coauthor of The Saboteurs

“A politician and a novelist, each an accomplished historian in his own right, are emerging as master authors of alternative history. In this ‘what if’ treatment of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Newt Gingrich and William Forstchen combine their talents to make the diplomacy as suspenseful as the combat, even for readers who know what happens next—or think they know. The authors’ mastery of both the broad sweep of events and the details of naval war and military technology give their counterfactual scenarios an unusual degree of plausibility, concluding with a version of the Japanese attack that guarantees a fictional Pacific war even more terrible than the one that began on December 7, 1941.”

—Dennis Showalter, former president of the

Society of Military Historians

“The book is not only a great read, it is a fascinating historical story that applies today in Iraq as it did in the Western Pacific in the late thirties and forties.”

—Captain Alex Fraser, USN (Ret.)

“The authors’ research shines in accurate accounts of diplomatic maneuvering as well as the nuts-and-bolts of military action.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Begins what will be a fascinating alternative history of the war in the Pacific.”

—The Roanoke Times (Virginia)

ALSO BY

NEWT GINGRICH AND WILLIAM R. FORSTCHEN

Gettysburg

Grant Comes East

Never Call Retreat

Pearl Harbor

DAYS

OF

INFAMY

NEWT GINGRICH,

WILLIAM R. FORSTCHEN,

AND ALBERT S. HANSER,

CONTRIBUTING EDITOR

THOMAS DUNNE BOOKS

ST. MARTIN’S GRIFFIN NEW YORK

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

THOMAS DUNNE BOOKS.

An imprint of St. Martin’s Press.

DAYS OF INFAMY. Copyright © 2008 by Newt Gingrich and William R. Forstchen.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America.

For information, address

St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue,

New York, N.Y. 10010.

All photographs are credited to the Naval Historical Center, and are in the public domain.

www.thomasdunnebooks.com

www.stmartins.com

The Library of Congress has catalogued the hardcover edition as follows:

Gingrich, Newt.

Days of infamy / Newt Gingrich and William R. Forstchen.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-312-36351-2

ISBN-10: 0-312-36351-6

1. World War, 1939–1945—Pacific Area—Fiction. 2. World War, 1939–1945—Campaigns—Fiction.

I. Title.

PS3557.I4945 D39 2008

813′.54—dc22

2008004743

ISBN-13: 978-0-312-56090-4 (pbk.)

ISBN-10: 0-312-56090-7 (pbk.)

First St. Martin’s Griffin Edition: August 2009

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For the men of the United States Navy who, in the dark days of 1941 and early 1942, held the Japanese and Nazi Empires at bay, while back home, an aroused America prepared itself to go forth to save the world. Those chosen few, frightfully outnumbered, facing opponents with vastly superior technologies, nevertheless did show the world that, as one Japanese admiral exclaimed, “The Americans have Bushido.”

“Now, who will stand on either hand and

keep the bridge with me?”

—“Horatius,” Thomas Babington, Lord Macaulay

Acknowledgments

This is our fifth book together with St. Martin’s Press, and whenever it has come to acknowledgments, we always find that to be a daunting task. Literally dozens have helped us along the way, from Tom LeGore and General Bob Scales with our Civil War series, up to our current efforts now focusing on the early days of World War II.

A beginning point of thanks should be with the team at St. Martin’s Press: our editor from the start, Pete Wolverton, our publisher, Thomas Dunne, and Pete’s valuable assistants, with a special mention for Elizabeth Byrne.

On “our side of the fence,” we have so many to thank. Our agent Kathy Lubbers, advisors such as Randy Evans, Stefan Passantino, Duane Ward, Liz Wood, our photo researcher Batchimeg Sambalaibat, and Rick Tyler. Captains Cuddington and Weisbrook who helped keep a watchful eye on various technical points, and “W. E. B. Griffin” III & IV., who have proven to be great and loyal friends… our standard running joke between us is “Gee, wish I had thought of that!”

Callista Gingrich has always been an inspiration, especially when I (Newt) have been locked away doing research, or during the long hours of writing and debating out ideas related to this book, and for Bill she has always been the most steadfast of friends, regardless of what hour he might call. Our technical editor, Steve Hanser and his wonderful wife Krys, as always, were there when most needed.

A special thanks to Sean Hannity and “Ollie” North for the interest they took in our book and to Duane Ward for organzing the special programming they dedicated to the launch of this series. We wish to thank as well the staff of professionals and volunteers at the National Memorial Park for the Arizona, at Pearl Harbor, along with the team that has worked so diligently to restore the pride of our fleet the USS Missouri and the museum built up around it, anchored now where the ill-fated Oklahoma came to rest at the bottom of the harbor. We also must mention the remarkable new facility on Ford’s Island, The Museum of Pacific Aviation. The special tour they gave us, pointing out evidence of the attack that was still clearly visible, was unforgettable. We recommend, as well, that if you ever visit our fiftieth state, do take the time to visit the “Punch Bowl,” sometimes referred to as the Arlington of the Pacific, where over 23,000 men and women who gave the last full measure of devotion during that war, rest in honored peace.

When the book Pearl Harbor was launched early in May 2007 we both went on a cross-country tour that finished up literally at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. It was a profoundly moving experience, for beyond the hurried routine of racing to book signings and events, we both had the opportunity to stop more than once, and hear the story of someone “who was there,” or remembered where they were and what they were doing when the news of what was happening at Oahu swept across our country. Some were children on the island on that dark day in 1941, others already in the military, and those moments were special to us and we cherished them. It was emotionally searing as we spent the last days of the tour looking out across that narrow harbor, slick with the oil still leaking from the Arizona, a wounded veteran still hemorrhaging after sixty-six years.

Sixty-six years, two thirds of a century have passed, and yet still the memory resonates in our culture, and we pray it always shall, a reason in part that we undertook the writing of these books, to present some of the great “what if’s” of that war but also as a reminder that

history does indeed repeat itself, and the price of freedom is indeed eternal vigilance.

And finally an acknowledgment to our daughters, Kathy, Jackie, and Meghan, who helped keep us on task, encouraged us along the way, and always showed their love for their fathers hard at work on this story.

Chapter One

The White House

December 7, 1941

19:45 hrs E.S.T.

PRESIDENT FRANKLIN DELANO Roosevelt looked up from the text of his speech as General George Marshall stood at the doorway, a flimsy sheet of telex printout clutched in his hand.

The President turned back to Missy LeHand, his secretary, pointing out where he had just crossed out a line for the address he was preparing for the nation, now scheduled for noon tomorrow before a joint session of Congress.

“Here, put this in the first sentence,” and he pointed to his margin notes, “‘a date which will live in infamy.’”

She nodded in agreement.

He now focused his attention on his Army chief of staff. “What do you have for us?”

“This just came in, Mr. President,” and Marshall stepped into the room, unfolding the telex sheet and handing it to him. “It reports that a third strike wave of at least seventy Japanese aircraft is attacking Pearl Harbor. The line went dead approximately ten minutes ago.”

The President scanned the few brief lines: “Oil tank farms struck. Fires out of control. Harbor channel blocked. Preparing to face invasion….” The message stopped in midsentence.

The President crumpled the report up, ready to angrily toss it on the floor by the side of his wheelchair, but then thought again. It was a document now, a moment of history, and he instead tossed it onto his desk, to be filed away for later. Attack the United States, would they? On our own soil? Without a declaration of war?

He thought about this dastardly sneak attack. What could this ever be compared to? Even when the British attacked and burned Washington and this very building to the ground, we knew we’d survive. Could this onslaught be but the beginning? Hitler was at the gates of Moscow. Might the Japanese turn on the Soviets as well, together those two dark powers finish off Stalin and then fling their entire fury at England and then us?

It was sobering to be the President presiding over the crisis of Western civilization and its death struggle with the forces of modern evil in both Europe and Asia. Our civilization must not lose this war, or it would be, indeed, as Winston Churchill said, “a thousand years of darkness.”

No, never think about the possibility of defeat, he thought to himself. If I allow that thought ever to take hold, it could permeate down across the entire nation. If ever America, if ever the entire free world, needed leadership that showed not just righteous anger, but also a firm, calm resolve that inevitable victory would come, it was now. Being an optimist was a trait he had acquired at Warm Springs, Georgia, when everyone else thought he should relax and accept that polio had crippled him and ended his political life. If he had given in eighteen years earlier, he would not be in the White House looking at General Marshall and dictating his most important speech to Congress.

No, he thought to himself, these Japanese will not turn me to thoughts of defeat, and neither will Herr Hitler. They have given us the possibility of bringing to bear the full force of our great people and the full resources of our great nation and now, after three years of quiet sustained effort, our preparedness program will show its results.

That strength had to be aroused through words. Words often meant more than ships and planes and tanks. It was words that aroused a people and focused a nation. He thought of his good friend across the Atlantic with fondness for his inspiring courage and language.

Though some of the more effete and cynical still privately shook their heads about Winston Churchill’s posturing and rhetoric, there would never be a denial that the strength of his words and his pugnacious defiance were worth as much as an entire army in the field and had braced England in the darkest days of its long history.

I must do the same. I must be the war President. I must lead. If I show weakness now, even for a moment, then surely darkness will triumph. In fact I must become the President of inevitable victory transcending the war.

He stirred from his thoughts and looked back at Marshall, who stood silent by the doorway into his office.

“Anything else?” the President asked, fixing Marshall with his gaze.

“Not much, sir. Most cable links to Hawaii are down. Apparently the terminus on Oahu was damaged. Our Army radio monitoring at the Presidio in San Francisco reports that it can still pick up a civilian station that is frantically calling for volunteers to donate blood, and for anyone with medical training to report to the nearest military base. World War One veterans with combat experience are to report, too. The Lightning Division and national guard units are mobilizing and preparing to repel any landing attempts, but it is still too early to tell what’s really happening.

“Other than that, sir, we are in the dark.”

“Have you talked to Admiral Stark?”

“Yes, sir. I must say he is still in shock. It is his fleet that has taken the brunt of the immediate punishment. The only good news is this: Our two carriers still based at Pearl Harbor were out to sea and for the moment are assumed to be safe.”

“Where are they now?”

“Halsey with Enterprise is believed to be somewhere southwest of Oahu. Lexington unfortunately is not in mutual support range; it is more than seven hundred miles to the northwest of Enterprise. They could hardly have been assigned farther apart. It was just random chance, sir, call it good luck or bad, with Halsey inbound after dropping planes off at Wake Island and Newton on Lexington outbound to Midway on the same mission. I just thank God they were not in the harbor this morning, which has usually been the typical routine.”

Roosevelt, a sailor and former undersecretary of the Navy, could picture the scenario and already had the potential answer. Along with Enterprise and Lexington being out at sea, a month back Saratoga had secretly transited back to the West Coast, for a refit in Bremerton, Washington, and was just preparing to head back out to Oahu.

As Marshall had just voiced, thank God the timing of all this regarding the aircraft carriers had worked out as it did, otherwise they would be burned-out hulks resting in the mud and flames of Pearl Harbor, along with the battleships.

“Do we even have a remote idea as to the size of the Japanese fleet that hit us?” Roosevelt asked.

Marshall shook his head.

“Apparently no one has yet organized a proper search. It could be four of their carriers; Admiral Stark thinks maybe five or six. There is no clear indication. We don’t even know what direction they came from.”

The President grunted at the lack of intelligence and analysis. “Surely we must do better than that,” he said to General Marshall, “and quickly.”

One of the first priorities would be to get Yorktown and Hornet transferred out to the Pacific. Together, five carriers could be a potent match-up with the Japanese—if Enterprise and Lexington survived the next few days.

That was a very big if.

He considered the distances, the obvious aggressiveness of the Japanese attack force. If he could step inside the mind of their admiral in command, whoever he was, chances were he would not be satisfied with the destruction inflicted so far. The third strike was proving that. A more timid soul would have made the surprise attacks of the morning and then pulled out. This opponent was in it for the kill.

“The Japs could move between our two carriers out there and finish each off in turn.”

“If their continued aggressiveness is any indication.” Marshall hesitated. “I am not a naval officer, sir, but yes, that would be my assessment.”

“I want those carriers to hit back, and hit them hard,” the President replied sharply. “If whoever launched this attack wishes to seek out our carriers, I expect ours not to turn tail and run, but to fight,” and he slapped the s

ides of his wheelchair. “To fight them, by God, and show them from the start that we intend to punch back.”

“I know Admiral Halsey, sir,” Marshall said quietly. “I think that is a foregone conclusion.”

The President nodded. He reached into his breast pocket, opened his cigarette case, inserted one into its holder, and lit it. Never in the history of American arms, in the history of the United States Navy, had such a defeat been dealt. Perhaps in the war against the Barbary pirates, when America’s only ship of the line, Philadelphia, had been lost, but not eight capital ships in one morning. And it was on his watch.

Now two carriers and what was left of the shattered fleet in Pearl, along with a couple of small task groups led by cruisers luckily out to sea as well this morning, were the only tools left to try and balance the ledger of this grim and terrible day. Later, thanks to the massive building program he and Carl Vinson had pushed through Congress during peacetime, there would be more than enough ships and planes. Last year he had called for fifty thousand planes to be built, more aircraft than existed in all the air forces of all the other nations now in this war. The factories to build them were still under construction, but soon the strength of America, would start to pour warplanes forth from those factories. Already tens of thousands of young men were in training to fly those planes yet to be built.

Come autumn of next year, a new fleet carrier would be sliding down the ways each month. Battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and submarines by the hundreds were under construction even now. But those forces were more than a year off. In the meantime, what can the Japanese, who have been preparing for years for this moment, do to us? Perhaps sweep the entire Pacific from the China coast to San Francisco and so entrench themselves that it could take a decade or more to push them back, if ever.

But it’s a year or more before we can even begin to replace our losses, until then we have to fight with what we have. This evening it all rests on two understrength carrier groups, their crews, and the as-yet-untested young men flying antiquated planes.

1945

1945 Collusion

Collusion Trump's America

Trump's America Shakedown

Shakedown A Nation Like No Other

A Nation Like No Other To Try Men's Souls - George Washington 1

To Try Men's Souls - George Washington 1 Pearl Harbor: A Novel of December 8th

Pearl Harbor: A Novel of December 8th Valley Forge: George Washington and the Crucible of Victory

Valley Forge: George Washington and the Crucible of Victory To Save America

To Save America Grant Comes East cw-2

Grant Comes East cw-2 Victory at Yorktown: A Novel

Victory at Yorktown: A Novel Days of Infamy

Days of Infamy The Battle of the Crater: A Novel (George Washington Series)

The Battle of the Crater: A Novel (George Washington Series) Breakout: Pioneers of the Future, Prison Guards of the Past, and the Epic Battle That Will Decide America's Fate

Breakout: Pioneers of the Future, Prison Guards of the Past, and the Epic Battle That Will Decide America's Fate Pearl Harbour and Days of Infamy

Pearl Harbour and Days of Infamy Pearl Harbour - A novel of December 8th

Pearl Harbour - A novel of December 8th Understanding Trump

Understanding Trump To Save America: Abolishing Obama's Socialist State and Restoring Our Unique American Way

To Save America: Abolishing Obama's Socialist State and Restoring Our Unique American Way